Entomologist and artist Barrett Klein researches the impact of sleep on bees and other insects. Barrett invited dozens of artists and scientists to join him in exploring this topic through a collectively-created “cabinet of insect dreams.”

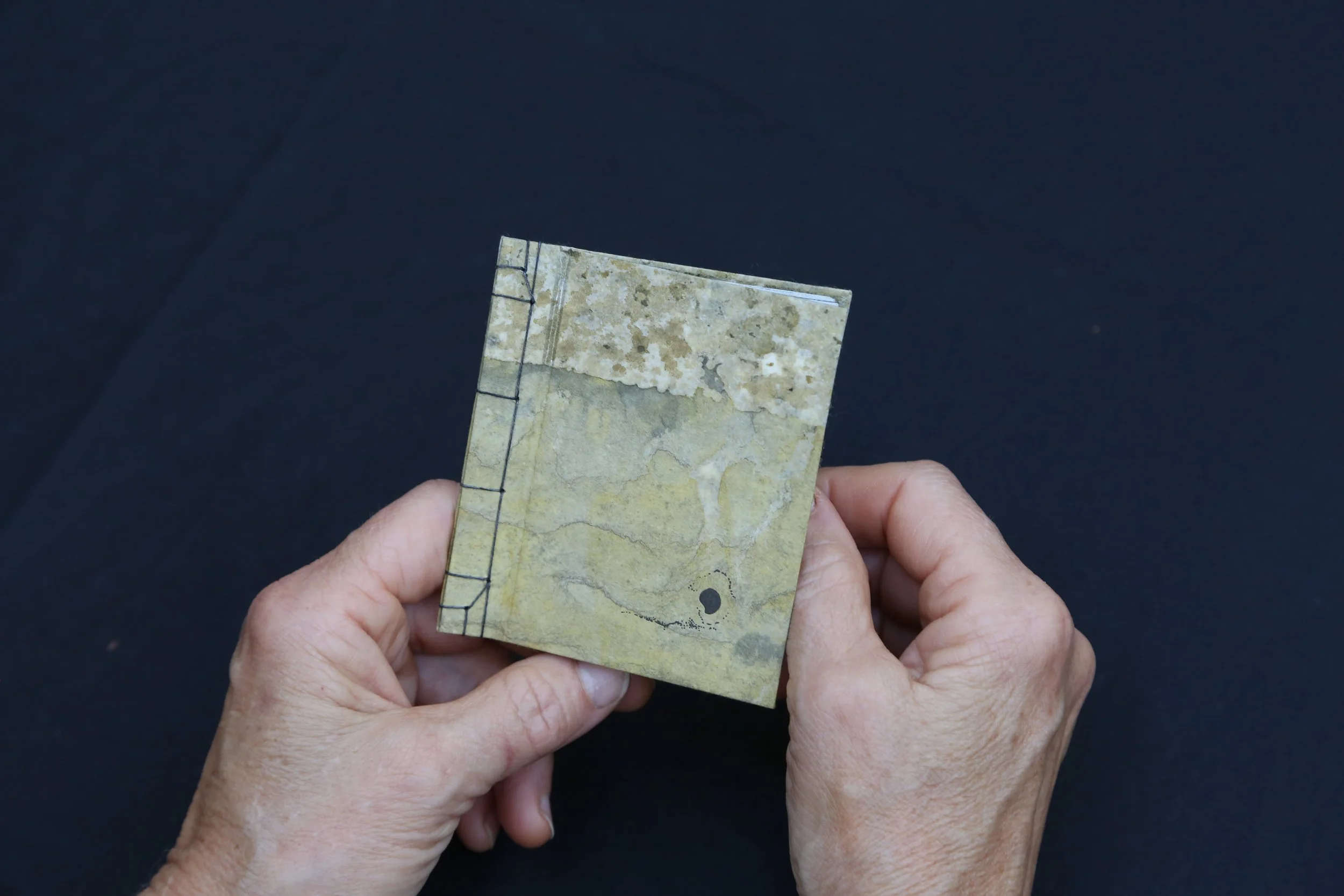

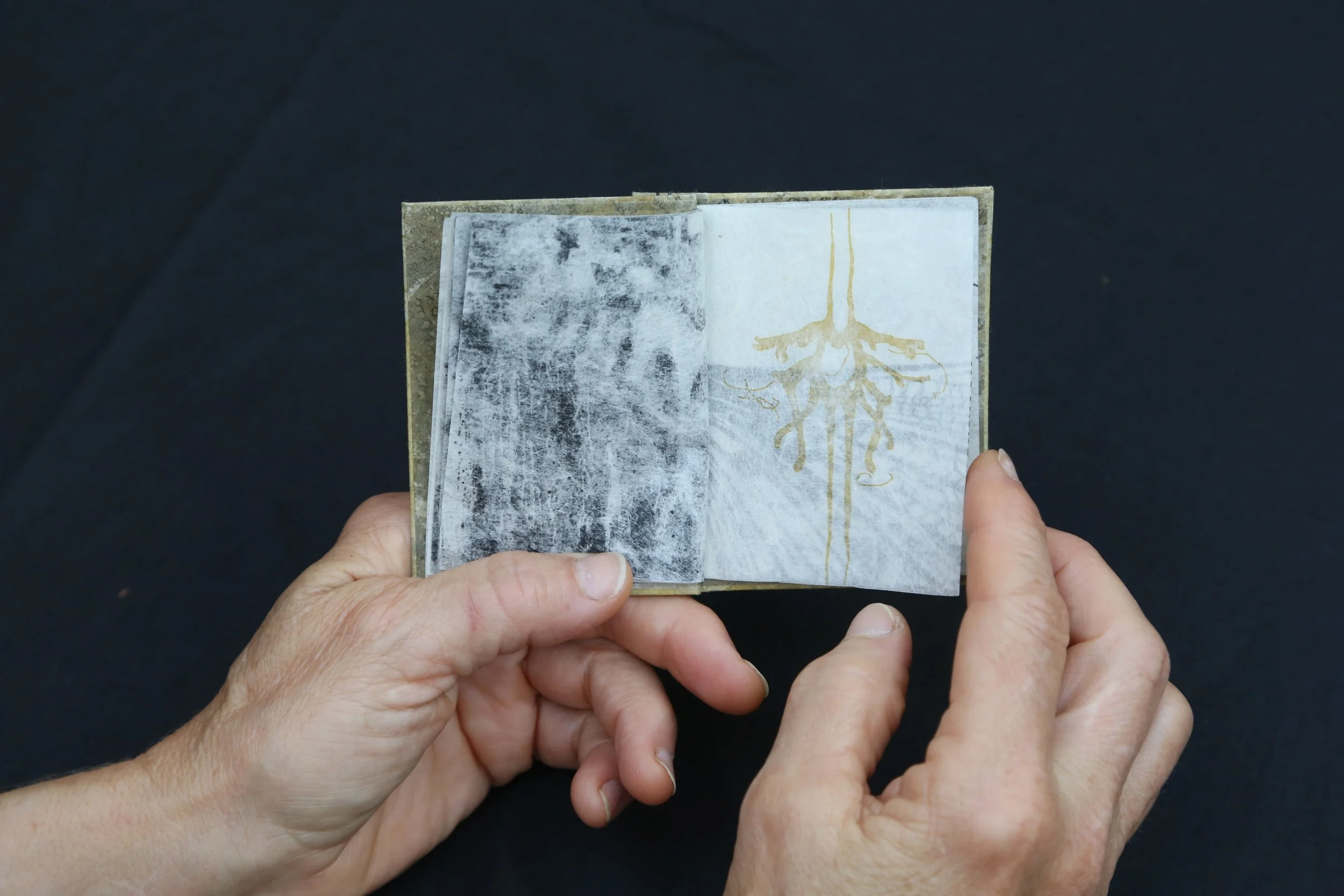

Tasked with making a book about insect dreams no larger than 5 x 3.5” (the size of the shelves on Barrett’s tiny homemade cabinet, and small enough to ship a copy to all other participating artists), I partnered with San Francisco-based book and printmaker Chelsea Herman.

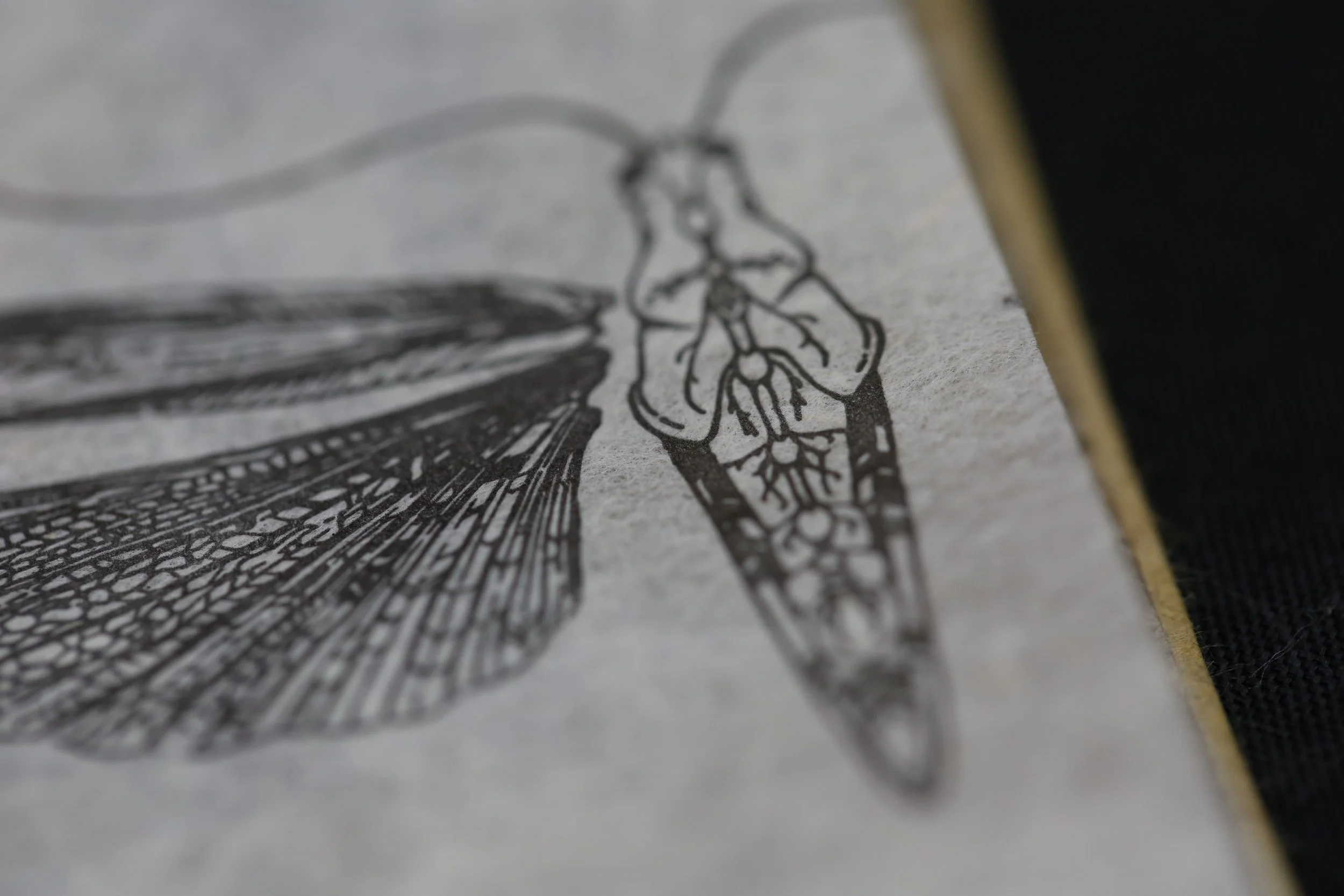

We decided to explore how interactions between pioneers and the now-extinct Rocky Mountain Locust shaped the western American landscape, in turn shaping a society’s dreams, memories, and evolving concept of “The West.” Our book layers imagery of dreams about locusts with patterns indicating the many societal and non-human systems tied up in this story of chaos and extinction.

Swarms of Rocky Mountain Locusts (Melanoplus spretus) devastated 19th century crops "with as much unconcern as if they had been a part of the elements,” according to one pioneer’s account. The swarms were mistaken for strange weather; described as fire, vapor, and the wrath of God. The insects ate through corn cobs, fences, and the shirts on farmers' backs. Females thrust their ovipositors into farmland until it was "perforated in all directions with innumerable holes."

As they swarmed, their bodies changed: nervous systems cued legs to swell with tensile strength and exoskeletons to turn yellow ochre.

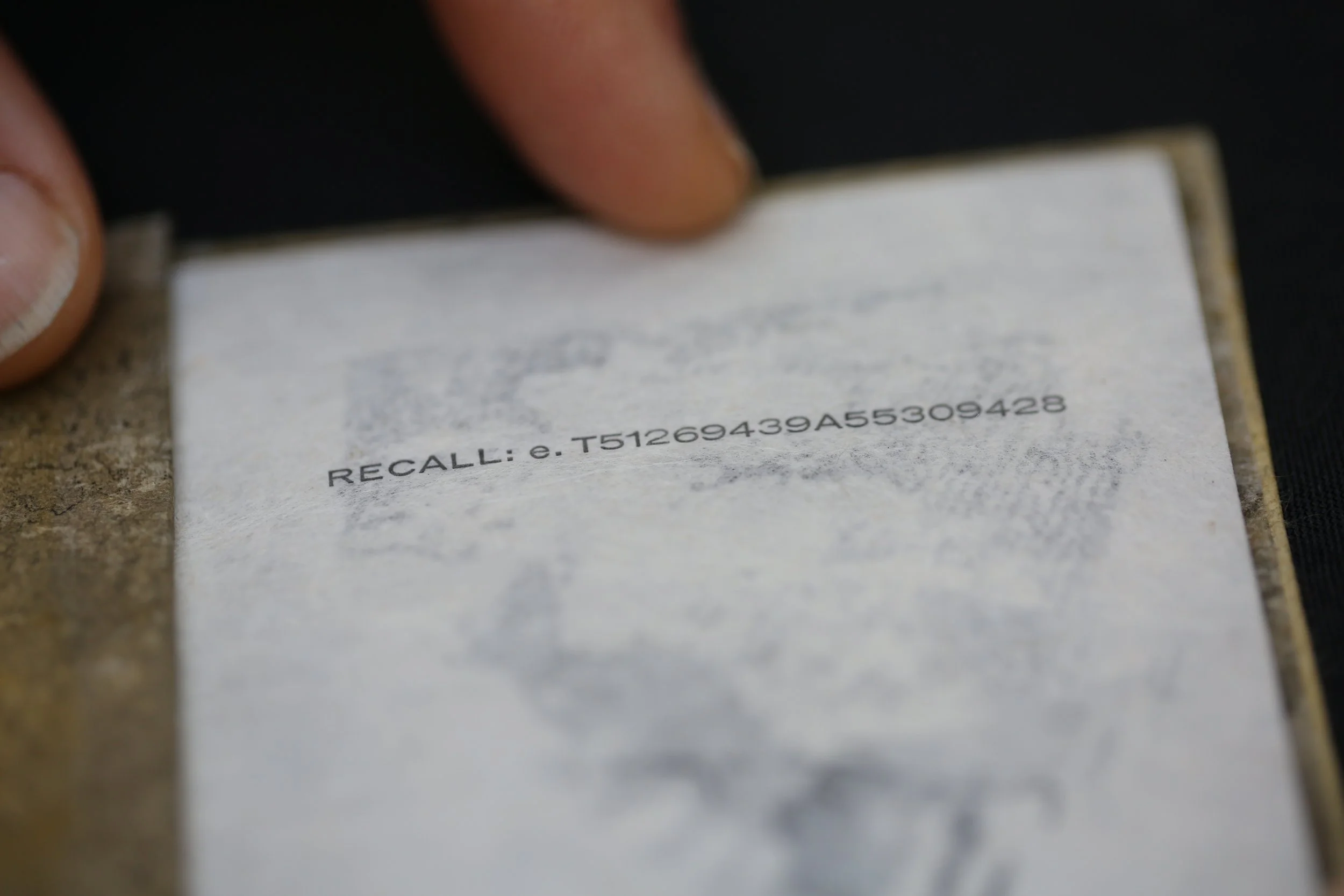

Ultimately the pioneers won the battle with the locusts, probably by plowing onward with their farming more-so than with their desperate tarring and burning techniques. The last swarms came in the 1870s and the last living specimen was collected in 1902, but e.T51269349A55309428 wasn't added to the IUCN Red List of extinct species until 2014.

The extinction is a testament to an era of extreme re-structuring of the landscape, on the part of humans and insects alike. Memories of this conflict may be marked by a kind of fading nightmare, while a more scientific account of what happened might rely largely on the few remaining specimens.

I poked a lot of holes, read up on related history and locust nervous systems, and drew a lot of patterns, but Chelsea's work really made the book. She made a lot of books, actually—about 40. Stitched them, set the teeny Bulmer lead type, letterpressed my ink drawings, and made incredible copperplate etchings of underground and swarm scenes.

We sent the copies off to Barrett, and in exchange received a box filled with dreams about everything from paper wasps to cochineal.

How do you interpret 'insect dreams'?